Eating Vichyssoise in Athens

by Geoffrey Wheatcroft

04.30.2010

Pascal Bruckner,

The Tyranny of Guilt: An Essay on Western Masochism (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010), 256 pp., $26.95.

Theodore Dalrymple

, The New Vichy Syndrome: Why European Intellectuals Surrender to Barbarism (New York: Encounter Books, 2010), 160 pp., $23.95.

“WHERE DID Europe Go?” shouted the cover of

Time’s continental edition earlier this year, not even bothering to add the word “Wrong.” Every kind of woe is said to be afflicting the European Union, and the great scheme of unification has shuddered to a halt. A concatenation of crises over the past few months, of which the near bankruptcy of the Greek state is only the most lurid, has heightened an urgent question of which direction, if any, the Continent is now taking.

In terms of the great implosion of the global economy which began on Wall Street in late 2008, the Greek financial collapse is a storm in a retsina glass. The sums concerned are trivial by the standards of modern multitrillion-dollar high finance, or indeed by the standards of the

Bundesbank. But the rights and wrongs are not the immediate point (even if no one can claim that successive Greek governments have managed public finances with any excess of scrupulosity: at one point they turned to the experts, in the form of Goldman Sachs, for lessons in creative accounting) so much as what the crisis has said about Europe.

A “DEEPENING” of the European Union is a long-standing project which has been visibly stalled for years now. In May 2004, the latest great expansion of the EU had seen the accession of ten new member states, of whom the eight that mattered were in Eastern Europe. Even those of us in some ways skeptical about the project—in the proper sense of the word “skepticism,” before it was purloined by the frankly xenophobic “Euroskeptics” of the Tory Party and London right-wing press—could not but be moved as Poles, Hungarians and Czechs, who had for so long been sundered from the West and suffered under the yokes of National and then Soviet Socialism, rejoined “our common European home.” Sad to say, after the celebration came the hangover. Europe woke up to realize that these new members now comprised a quarter of the enlarged EU’s population, while providing about one-twentieth of its gross product; and you don’t need an economics doctorate to see what a problem that meant.

By what in hindsight may seem hubristic timing, the following October a new European constitution was signed by all the member states—which is to say, by their political representatives. The rules require (to the regret of many Eurocrats, one cannot doubt) that such agreements should be ratified in each country, either by parliament or by popular referendum. This has meant that over and again grandiose schemes for taking the EU closer toward political federation have been elaborately worked out by officials in Brussels and subscribed to by heads of government, only to be rejected by the voters in one country or another, who are then told, in the best spirit of modern European democracy, to go back and vote again until they get it right.

In the spring of 2005, the Dutch and, more importantly, the French electorates rejected the constitution. It was no coincidence at all that these votes came within a year of that Eastern enlargement: on behalf of so many Europeans, the French were expressing disquiet about their new neighbors, personified by the proverbial Polish plumber taking their jobs. And they were saying even more emphatically that they did not want any further expansion; above all not to Turkey.

Behind this turmoil lay a malaise, a sense that all was not well, despite an unprecedented six decades of peace and prosperity. Since the fifteenth century, the world has been dominated by Europe and taught by Europe and exploited by Europe and made by Europe. After the calamitous experiences of the first half of the twentieth century, Europe had had enough, not least of itself and its own recent history.

But now the project, which began with the 1951 Treaty of Paris establishing the European Coal and Steel Community and proceeded through the 1957 Treaty of Rome, has come to an indefinite pause. The 2007 Treaty of Lisbon, designed to stick together all the pieces of the rejected constitution and renew the eu’s goal of healing the wounds of war, totalitarianism, mass murder and ethnic cleansing, has done little in practice to enhance the likelihood of a federalist European state.

IN SHORT, there has been a quite-remarkable lack of solidarity among the nations composing the EU. We have seen this no more clearly than in the bitter animosity that has erupted between Greece and Germany—the one country rich enough to bail out its feckless continental cousins. Although such bailing out is forbidden under sundry EU treaties and regulations, Europe has in practice always shown considerable ingenuity when rules needed to be bent, and something could have been arranged to effect a comparatively painless resolution.

There has instead been a spasm of mutual loathing. “Betrüger in der Euro-Familie” screeches the cover of the German magazine

Focus above a drooping statue of Venus, intending that Greece is this swindler in the European family, while in return a Greek paper, in defiance of all polite Euro-convention, uses as an illustration the likewise-statuesque figure atop the

Reichstag building, holding in her right hand a swastika. Vulgar as this might seem, the truth is that the zealous exponents of European integration all along overlooked mere public opinion. From the founding fathers on, the leaders who created this project have always moved much faster and farther in promoting unified institutions (or merely in proclaiming a

communautaire spirit of togetherness) than their electorates.

Bringing together the various European nations was surely a noble enterprise, and the European Union has obviously done huge good for most Europeans. So why don’t they like it—and each other—more? Behind these latest rows, institutional paralysis, and financial incompetence (not to say, downright dishonesty) of some governments, the scars of war have plainly not all been healed. Still, these squabbles, however nasty, of course could be temporary. Yet might it be that “Europe” rests on shakier foundations? Is there a deeper collapse of European self-confidence?

IN

THE Tyranny of Guilt, Pascal Bruckner argues that Europe’s crisis is even worse than it appears and is ignored at the Continent’s peril. The French novelist and essayist is less concerned with the immediate political woes of Brussels and Strasbourg than with a collapse of self-confidence and a spirit of self-flagellation he finds among the former colonizers and masters of the world. This is supposedly manifested in various ways: a drop in the birthrate so drastic that populations are no longer growing and will soon decline in Spain and Italy; a reflexive hostility to the United States, and also to Israel; a self-hating or “miserablist” narrative of national and continental history; and a groveling, guilt-induced refusal to take seriously the threat from militant Islam, a threat which comes not only from as far away as Iran and Afghanistan but more and more from within, as greatly increased Muslim populations challenge, not only by their numbers, but also by their vigor and sometimes their violence, a post-Christian Europe which doesn’t believe in itself anymore and too often retreats into sour

Trotzreaktionen.

Even those who disagree with Bruckner’s thesis must admit that he makes some good points, and lands palpable hits, although some on what might be called soft targets. There is certainly some degree of latent anti-Americanism lurking on the Continent. But by now there really should be no need to chastise, as Bruckner does, those Europeans from the would-be cultural elite who actually gloated over the September 11 mass murder. They were always a cranky minority, whose bitterness has little to do with the real—often justifiable—basis for skepticism about American policies and actions. Bruckner cites two such characters, both now late and only partly lamented: Jean Baudrillard, a French pseudo-

penseur who called the destruction of the Twin Towers an “absolute event” and a reflection of an antagonism “which points past the spectre of America”; and Karlheinz Stockhausen, the German avant-garde composer, for whom it was “the biggest work of art there has ever been.” My personal response to that was a resolve never again to read a word by Baudrillard or listen to a bar of Stockhausen’s music. In these hard times we must all make sacrifices.

Now, Bruckner knows very well that most Europeans felt nothing but sympathy with America on that indelible day. What they didn’t realize was how the horror would be used to trigger (rather than justify) a completely irrelevant—not to say illegal, needless and disastrous—invasion of Iraq. If the overwhelming European sense of identity with and support for the United States has been dissipated these past eight years, whose fault is that?

When Bruckner mocks the notion of “Islamophobia” as it is now used by the softer-headed European liberal Left to deflect any criticism of Muslims, peaceable or violent, as a form of bigotry supposedly akin to racism, he is on firmer ground. The very concept requires “the crudest confusion between a religion, a specific system of belief, and the faithful who adhere to it.” This willful elision of religion and race is an obvious category mistake fueled by deliberate intellectual dishonesty: criticizing any religion, whoever practices it, is not “racism.”

To be sure, there is sometimes an inevitable confusion of people and faith. From the early nineteenth century on, Irish nationalism was a movement representing the Catholic masses. There was much coarse prejudice against the Irish, in England and then in America when they began to migrate there, which was mingled with the old war cry of “anti-popery.” But rejecting such brutish bigotry doesn’t mean accepting that Irish nationalism must be entirely right, still less that the Roman Catholic Church must be beyond criticism.

On the whole, liberals and radicals did manage to make that distinction clear, some of the time, but their support for the Irish cause still led them astray. In his book

Paddy and Mr. Punch, that fine Irish historian R. F. Foster has described the various excuses and evasions to which the Left has resorted when dealing with Ireland since the creation of the Free State nearly ninety years ago, adding drily that anyone can see the psychological reason for this, since “it is difficult, if not morally impossible, for the Left to admit that an independent Irish state has become so decisively different from the Left’s vision of what it should be.”

Today, there are some on the left who seem to find it just as difficult to acknowledge that the outcome of Arab nationalism and decolonization has not been “what it should be,” that too many Arab states are corrupt autocracies at best and murderous theocracies at worst. Our sub-intelligentsia also forgets at times that what Shelley called “bloody Faith, the foulest birth of time” is just as foul in the name of Muhammad as of Jesus.

A painful confusion in Europe about how to deal with Muslims is further complicated by the question of Israel, the target of ever-increasing European obloquy. Bruckner is honest enough to concede that, just as reasoned criticism of the Muslim religion isn’t abase hatred called Islamophobia, so too reasoned criticism of Israel cannot be dismissed with another charge. “Yes, It’s Anti-Semitic” read the headline on Eliot A. Cohen’s

Washington Post column four years ago denouncing

The Israel Lobby and U.S. Foreign Policy by John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt. Actually, that book might be faulted in detail, or possibly its whole thesis might be disputed. But, no, it’s not anti-Semitic.

As Bruckner rightly says, “this monomaniac obsession with the Near East” at once “allows the Arab world to transform the Jewish state into a convenient diversion from its wretchedness and its frustrations,” while allowing Europe “to clear itself of its past offenses.” That’s not to mention the fatuous and sometimes-numerous wild comparisons he cites, which seem to confirm his view that Europe is wildly overcompensating for its colonial and fascist sins. A choice case is Rosa Plumelle-Uribe, who assures us that “there is a dynamic relationship between the destruction of the natives of America, the annihilation of the Blacks, and the policies of extermination introduced by the Nazis.”

As you might guess, she would be a French intellectual. But then so is Bruckner, not all of whose pages are light reading. France “has long lived under a system of deferred truth,” he says, “struggling to unveil the secrets that have been fermenting like a puddle of pus for years, because the regalian state, with its twofold Catholic and monarchical heritage, is the depository of the true and the false.” Some blame may attach to the translator, but he can’t have had an easy task. Literary French, like German in another way, has a decidedly more exalted and less conversational flavor than English, and it requires great skill to avoid such pomposity.

In the end, Bruckner’s real theme is something deeper and broader: Western guilt and the resulting lack of self-belief. Again, he sees the origins of this in a guilty conscience, and there is an echo here of debates sixty or more years ago over Communism. As the more perceptive anti-Stalinists such as Orwell and Camus recognized, the West’s position had been compromised by a loss of nerve, or by a bad conscience about the harsh injustices of capitalist society which was far from unfounded. Nor is another Western guilt—stemming from European dispossession and colonialism throughout much of the world—without foundation either. There may be a further echo. The true moral reckoning with Communism came from those who had lived under it, and it may be that we will only hear honest sense about what Europe did to the rest of world, and what happened when Europe went home, from those who live in Asia and Africa, after they have come to terms with that legacy.

SECONDING BRUCKNER in these polemics—European self-hatred, unthinking anti-Americanism, servile deference to Islam—comes the English writer “Theodore Dalrymple,” the not entirely plausible pen name (dreamed up, its user has said, to sound like a dyspeptic, grumpy old man glaring out of the window of his London club as he sips his port) of Anthony Daniels, who also writes under that real name, and who is one of the more interesting and provocative conservative commentators of the age. His targets are familiar enough from such debate: multiculturalism, political correctness, moral relativism, what Robert Hughes has called the culture of complaint, the substitution of “rights” for civic and social obligation, the catastrophic implosion of the underclass, and whatnot.

All of that could sound a little wearisome by now, but what makes Dalrymple–Daniels valuable is his background, and his experience. His father was a Communist, his mother, a Jewish refugee from Germany (nothing so extraordinary there in neoconservative terms, come to think of it), but he also knows Africa well, and has spent his life as a doctor and psychiatrist working not least in some of the grimmest English prisons. And so in those political-cum-culture wars he is no chicken hawk or armchair warrior. He has been in the trenches and knows whereof he speaks.

Even so,

The New Vichy Syndrome is not his happiest contribution, from its title on: quite how Europe as a whole today, with all its failings, is

vichyssois is not at all clear. Whatever compromises Europeans are making in the face of immigration and social change, or whatever reluctance they may show about waging a so-called war on terror to the hilt, it scarcely compares with the deliberate national self-abnegation of Marshal Philippe Pétain in the face of superior military power and his subsequent policy of collaboration.

Oddly enough, although Dalrymple denounces “Anthony Blair. . . . A man of consummate dishonesty,” Iraq is mentioned only once in the book, and the author doesn’t suggest, as he might have done and as many English people feel, that Blair was the nearest thing to an English Pétain. If that sounds a little hyperbolic, it’s the theme of

The Ghost, Robert Harris’s highly enjoyable thriller-with-attitude which has now been filmed as

The Ghost Writer, an undisguised portrait of a prime minister who at all times saw his duty as serving the national interest—of another country.

When Dalrymple writes that “Western Europe is in a strangely neurotic condition, of being smug and anxious at the same time,” wanting “as of right, both security and luxury in a world that neither can nor wants to grant it either,” few honest Europeans will deny the words. But does that mean that Europe is dying of inanition, or that, lacking such security, it will succumb not to war but to internal decay, and to a new demographic revolution? Even if the perverse effects of universal welfare in creating a demoralized and degraded underclass are as Dalrymple describes them, we are not going to return, and don’t want to return, to the days of mass destitution, any more than we are going to send our Muslim citizens back to Africa and Asia.

IF A partly imaginary “Islamophobia” is one problem, another is the exaggerated conservative fear that Europe is under threat of Islamization, even if it has long antecedents. In a flight of fancy, Edward Gibbon imagined a different outcome to the eighth-century incursion of the rampant forces of newborn Islam into Europe, as far north as Poitiers in central France, where they were halted only by defeat in battle. Otherwise they might have reached Scotland and Poland, Gibbon wrote in

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, and “perhaps the interpretation of the Koran would now be taught in the schools of Oxford, and her pulpits might demonstrate to a circumcised people the sanctity and truth of the revelation of Mahomet.”

This fantasy has been revisited by neoconservative writers and polemicists, in books with such lurid titles as

The Daily Mail columnist Melanie Phillips’s

Londonistan and the American journalist Christopher Caldwell’s

Reflections on the Revolution in Europe. Not only has Europe acquired for the first time ever a very large Muslim population, it has made no serious effort to assimilate it, at any rate not in the way, and not with the success, that the United States has always absorbed its huddled masses. Given the respective birthrates, Muslims can only become an ever-larger minority, many of whom, or so it is apprehended, will simply not consider themselves true citizens of France or Great Britain.

This has been badly handled by Europe, Dalrymple rightly says, and the Continent needs to think how it can absorb its new Muslim citizens. Even alleged liberals fretful about “Islamophobia” can’t be happy about arranged marriages which are sometimes plainly coercive, still less “honor killings” of girls from Muslim families who have chosen the wrong boy, something Dalrymple has observed near at hand. But after one or two such well-aimed shots, Dalrymple’s mordant spirit can carry him away, as when he cheerfully tells us that Muslim youths “regard young white women in Britain, not without good reason, as vulgar sluts.” And when he writes that the British defeat of China in the nineteenth-century Opium Wars “must surely be applauded by all those who believe in man’s inalienable right to intoxicate himself with anything he pleases. In this respect, the war certainly led to an increase in freedom for the average Chinese,” he is taking paradox mongering just a little too far.

BOTH MEN think that Europe must recover the old self-confidence with which it once fashioned the world, if not to that end, and should not be ashamed of emulating America, for this loss of nerve explains the “Depression in Paradise,” as Bruckner calls one chapter. He lambastes his own country’s culture of complaint—“everything that is going wrong in France is due to the malice of foreign powers”—but he goes much too far the other way. France has after all recently been faced by an economic crisis which was mostly the responsibility of Wall Street and Washington, and weathered it better than most countries. Europeans no longer like war, says Bruckner, “and we leave to others the task of waging it.” But which war? Few Europeans wanted to fight the one in Iraq, and most Americans now agree.

As to Bruckner’s saying that “without American help in 1917, and especially in 1944, [Europe] would have been purely and simply wiped off the map,” this is sheer

néo-connerie. The idea that the United States was the savior of Europe in World Wars I and II is popular in some circles on both sides of the Atlantic, but is demonstrably false. Between the formal entry of the United States into the Great War in April 1917 and the last German offensive in March 1918, hundreds of thousands of Entente soldiers were killed, mainly British in the summer and autumn of 1917 after the frightful slaughter of the French army in the spring; and in that period of nearly a year, fewer than two hundred Americans died. In the course of that war, the Frenchmen killed defending their country were twice as numerous as all the Americans who have died in every foreign war taken together from 1776 until today. As a matter of historical fact, the Third Reich was defeated by the Red Army and not by the Western democracies. Even though over one hundred thirty-five thousand American GIs died—a startling figure today—between D day and V-E day, more than half a million Russians were killed.

At the end, Bruckner writes that it’s time for Europe and America to reconnect, and so say all of us. But then, it takes more than one to tango, and a renewal of transatlantic ties will require a change on both sides. We had eight years of a Clinton administration which was inept about working with Europe, followed by eight of a Bush administration which was contemptuous toward the Continent except when it made itself useful to American ends. Now we have a president of whom Roger Cohen observes in the

International Herald Tribune that at heart, he “is not a Westerner, not an Atlanticist.” Where did Europe go? is doubtless one question; but another is: where is America?

(click on this or any image in this essay to see a clearer and bigger version of the image).

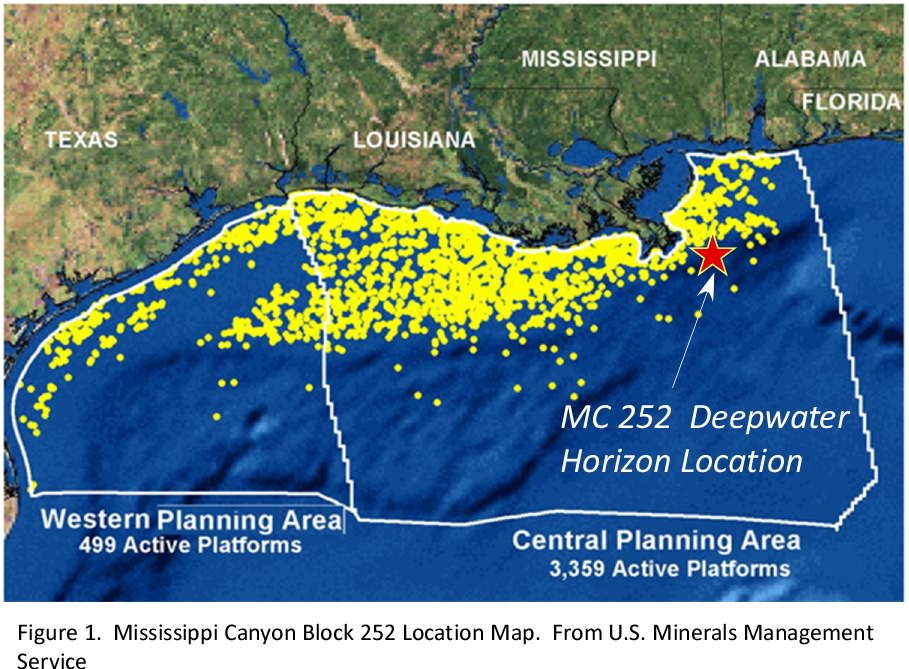

(click on this or any image in this essay to see a clearer and bigger version of the image). The oil spill is occurring within the "Macondo prospect", which is located in Mississippi Canyon Block 252 in the Gulf of Mexico.

The oil spill is occurring within the "Macondo prospect", which is located in Mississippi Canyon Block 252 in the Gulf of Mexico. This shows the relation of Block 252 to nearby sites:

This shows the relation of Block 252 to nearby sites:

And this is the definitive high-resolution map showing block 252 in comparison with other prospects in the Mississippi Canyon area and surrounding areas.

And this is the definitive high-resolution map showing block 252 in comparison with other prospects in the Mississippi Canyon area and surrounding areas.

Here is an image - courtesy of NOAA's GeoPlatform service - showing the topography surrounding the leaking wellhead:

Here is an image - courtesy of NOAA's GeoPlatform service - showing the topography surrounding the leaking wellhead:

Nearly two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, publics of former Iron Curtain countries generally look back approvingly at the collapse of communism. Majorities of people in most former Soviet republics and Eastern European countries endorse the emergence of multiparty systems and a free market economy.

Nearly two decades after the fall of the Berlin Wall, publics of former Iron Curtain countries generally look back approvingly at the collapse of communism. Majorities of people in most former Soviet republics and Eastern European countries endorse the emergence of multiparty systems and a free market economy. The acceptance of — and appetite for — democracy is much less evident today among the publics of the former Soviet republics of Russia and Ukraine, who lived the longest under communism. In contrast, Eastern Europeans, especially the Czechs and those in the former East Germany, are more accepting of the economic and societal upheavals of the past two decades. East Germans, in particular, overwhelmingly approve of the reunification of Germany, as do those living in what was West Germany. However, fewer east Germans now have very positive views of reunification than in mid-1991, when the benchmark surveys were conducted by the Times Mirror Center for the People & the Press. And now, as then, many of those living in east Germany believe that unification happened too quickly.

The acceptance of — and appetite for — democracy is much less evident today among the publics of the former Soviet republics of Russia and Ukraine, who lived the longest under communism. In contrast, Eastern Europeans, especially the Czechs and those in the former East Germany, are more accepting of the economic and societal upheavals of the past two decades. East Germans, in particular, overwhelmingly approve of the reunification of Germany, as do those living in what was West Germany. However, fewer east Germans now have very positive views of reunification than in mid-1991, when the benchmark surveys were conducted by the Times Mirror Center for the People & the Press. And now, as then, many of those living in east Germany believe that unification happened too quickly. One of the most positive trends in Europe since the fall of the Wall is a decline in ethnic hostilities among the people of former communist countries. In a number of nations, fewer citizens say they hold unfavorable views of ethnic minorities than did so in 1991. Nonetheless, sizable percentages of people in former communist countries continue to have unfavorable views of minority groups and neighboring nationalities. The new poll also finds Western Europeans in a number of cases are at least as hostile toward minorities as are Eastern Europeans. In particular, many in the West, especially in Italy and Spain, hold unfavorable views of Muslims.

One of the most positive trends in Europe since the fall of the Wall is a decline in ethnic hostilities among the people of former communist countries. In a number of nations, fewer citizens say they hold unfavorable views of ethnic minorities than did so in 1991. Nonetheless, sizable percentages of people in former communist countries continue to have unfavorable views of minority groups and neighboring nationalities. The new poll also finds Western Europeans in a number of cases are at least as hostile toward minorities as are Eastern Europeans. In particular, many in the West, especially in Italy and Spain, hold unfavorable views of Muslims. As for the Russians themselves, there has been an upsurge in nationalist sentiment since the early 1990s. A majority of Russians (54%) agree with the statement “Russia should be for Russians”; just 26% agreed with that statement in 1991. Moreover, even as they embrace free market capitalism, fully 58% of Russians agree that “it is a great misfortune that the Soviet Union no longer exists.” And nearly half (47%) say “it is natural for Russia to have an empire.”

As for the Russians themselves, there has been an upsurge in nationalist sentiment since the early 1990s. A majority of Russians (54%) agree with the statement “Russia should be for Russians”; just 26% agreed with that statement in 1991. Moreover, even as they embrace free market capitalism, fully 58% of Russians agree that “it is a great misfortune that the Soviet Union no longer exists.” And nearly half (47%) say “it is natural for Russia to have an empire.” While the current polling finds a broad endorsement for the demise of communism, reactions vary widely among and within countries. In east Germany and the Czech Republic, there is considerable support for the shift to both a multiparty system and a free market economy. The Poles and Slovaks rank next in terms of acceptance. In contrast, somewhat fewer Hungarians, Bulgarians, Russians and Lithuanians say they favor the changes to the political and economic systems they have experienced, although majorities or pluralities endorse the changes. Ukraine is the only country included in the survey where more disapprove than approve of the changes to a multiparty system and market economy.

While the current polling finds a broad endorsement for the demise of communism, reactions vary widely among and within countries. In east Germany and the Czech Republic, there is considerable support for the shift to both a multiparty system and a free market economy. The Poles and Slovaks rank next in terms of acceptance. In contrast, somewhat fewer Hungarians, Bulgarians, Russians and Lithuanians say they favor the changes to the political and economic systems they have experienced, although majorities or pluralities endorse the changes. Ukraine is the only country included in the survey where more disapprove than approve of the changes to a multiparty system and market economy. Opinions among east Germans about the impact of unification on their lives are consistent with one of the most striking trends observed in the new survey. People in former communist countries now rate their lives markedly higher than they did in 1991, when they were still coming to grips with the massive changes then taking place. This is true even in countries where overall levels of satisfaction with life — as well as positive assessments of political and economic changes — are significantly lower than in the most upbeat of the nations surveyed.

Opinions among east Germans about the impact of unification on their lives are consistent with one of the most striking trends observed in the new survey. People in former communist countries now rate their lives markedly higher than they did in 1991, when they were still coming to grips with the massive changes then taking place. This is true even in countries where overall levels of satisfaction with life — as well as positive assessments of political and economic changes — are significantly lower than in the most upbeat of the nations surveyed. While the current survey finds people in former communist countries feeling better about their lives than they did in 1991, the increases in personal progress have been uneven demographically, as has been acceptance of economic and political change. There are now wide age gaps in reports of life satisfaction. In Poland, for example, half of those younger than age 30 rate their lives highly, compared with just 29% of those ages 65 and older. These gaps were not evident in 1991, when all age groups expressed comparably negative views of their lives. The same pattern is evident among all of the former communist publics surveyed.

While the current survey finds people in former communist countries feeling better about their lives than they did in 1991, the increases in personal progress have been uneven demographically, as has been acceptance of economic and political change. There are now wide age gaps in reports of life satisfaction. In Poland, for example, half of those younger than age 30 rate their lives highly, compared with just 29% of those ages 65 and older. These gaps were not evident in 1991, when all age groups expressed comparably negative views of their lives. The same pattern is evident among all of the former communist publics surveyed. An urban-rural gap also is evident in life satisfaction in two principal republics of the former Soviet Union included in the poll — Russia and Ukraine — as well as in Bulgaria and Hungary. In Ukraine, for example, 30% of urban dwellers express high satisfaction with their lives, compared with just 17% of those residing in rural areas. These disparities in reports of well-being were not apparent two decades ago. Then, on average, people were less happy, but there were no significant demographic differences in their opinions.

An urban-rural gap also is evident in life satisfaction in two principal republics of the former Soviet Union included in the poll — Russia and Ukraine — as well as in Bulgaria and Hungary. In Ukraine, for example, 30% of urban dwellers express high satisfaction with their lives, compared with just 17% of those residing in rural areas. These disparities in reports of well-being were not apparent two decades ago. Then, on average, people were less happy, but there were no significant demographic differences in their opinions. The survey also shows substantial differences in acceptance of democratic values among people in former communist countries. While majorities in most countries approve of the transition to a multiparty system, it remains a rocky transition in many countries. The appeal of a strong leader over a democratic form of government is evident in Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Hungary. Only in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and the former East Germany do most people believe that a democratic form of government is the best way to solve the country’s problems.

The survey also shows substantial differences in acceptance of democratic values among people in former communist countries. While majorities in most countries approve of the transition to a multiparty system, it remains a rocky transition in many countries. The appeal of a strong leader over a democratic form of government is evident in Russia, Ukraine, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Hungary. Only in Poland, the Czech Republic, Slovakia and the former East Germany do most people believe that a democratic form of government is the best way to solve the country’s problems. Beyond the economy, crime, corruption and drugs are widely seen as major problems in each of the former communist countries surveyed. The environment, the poor quality of schools, and the spread of AIDS and other infectious disease are also common concerns in all countries.

Beyond the economy, crime, corruption and drugs are widely seen as major problems in each of the former communist countries surveyed. The environment, the poor quality of schools, and the spread of AIDS and other infectious disease are also common concerns in all countries. The Roma, or Gypsies, continue to stand out as the most widely disliked ethnic group. More than eight-in-ten Czechs (84%) hold an unfavorable view of them, as do 78% of Slovaks and 69% of Hungarians. Many of the expressed antagonisms reflect historic enmity with neighboring peoples, or long-standing dislike of religious or ethnic minorities. In Hungary, 33% have an unfavorable opinion of Romanians, and 29% say they dislike Jews. Many Poles have a negative opinion of Russians (41%), Ukrainians (35%) and Jews (29%). A sizable number of Lithuanians hold unfavorable views of Poles (21%), but many more dislike Jews (37%). More than one-in-four Slovaks (27%) express a negative opinion of Jews.

The Roma, or Gypsies, continue to stand out as the most widely disliked ethnic group. More than eight-in-ten Czechs (84%) hold an unfavorable view of them, as do 78% of Slovaks and 69% of Hungarians. Many of the expressed antagonisms reflect historic enmity with neighboring peoples, or long-standing dislike of religious or ethnic minorities. In Hungary, 33% have an unfavorable opinion of Romanians, and 29% say they dislike Jews. Many Poles have a negative opinion of Russians (41%), Ukrainians (35%) and Jews (29%). A sizable number of Lithuanians hold unfavorable views of Poles (21%), but many more dislike Jews (37%). More than one-in-four Slovaks (27%) express a negative opinion of Jews. Views of Russia differ widely across the surveyed countries. Many of Russia’s neighbors in Eastern Europe see its influence as a bad thing, perhaps reflecting concern over resurgent nationalism in Russia.

Views of Russia differ widely across the surveyed countries. Many of Russia’s neighbors in Eastern Europe see its influence as a bad thing, perhaps reflecting concern over resurgent nationalism in Russia. The long-existing transatlantic divide in attitudes toward the role of the state in society has grown over the past two decades. In nine of the 13 European countries surveyed, fewer people today than in 1991 think that people should be free to pursue their life’s goals without interference from the state. Only in Britain and Italy have the proportions expressing this view increased. However, Italians and the British are still more supportive of an active role for the state in society than are Americans. The least support for a laissez-faire government is in Lithuania (17%) and in Bulgaria (23%).

The long-existing transatlantic divide in attitudes toward the role of the state in society has grown over the past two decades. In nine of the 13 European countries surveyed, fewer people today than in 1991 think that people should be free to pursue their life’s goals without interference from the state. Only in Britain and Italy have the proportions expressing this view increased. However, Italians and the British are still more supportive of an active role for the state in society than are Americans. The least support for a laissez-faire government is in Lithuania (17%) and in Bulgaria (23%). British wariness of the Brussels-based European Union persists and could be worsening. The British are evenly split on whether membership in the European club is a good thing. And the proportion of the British population that thinks the EU has had a good influence on the way things are going in their country is lower in 2009 than in 2002. That is also the case in France and Italy.

British wariness of the Brussels-based European Union persists and could be worsening. The British are evenly split on whether membership in the European club is a good thing. And the proportion of the British population that thinks the EU has had a good influence on the way things are going in their country is lower in 2009 than in 2002. That is also the case in France and Italy.